Thoughtful measurements and evaluations tied to clear learning goals are a vital, motivating part of music education. For students, the right assessments demonstrate their growth as musicians and provide an encouraging path forward. For educators, assessments provide valuable information that can be used to inform and adapt their teaching.

Marshall Haning is associate professor and area head of Music Education at the University of Florida School of Music. He also serves as chair of the faculty for the UF College of the Arts; convenor of the Assessment, Measurement, and Evaluation Special Interest Group for the International Society of Music Education; and chair of the International Symposia on Assessment in Music Education. He teaches undergraduate and graduate courses, including sections of the “Assessing Music Learning” course in the online Master of Music in Music Education (MMME) program. Before coming to UF, he taught high school choir and music theory.

Marshall Haning is associate professor and area head of Music Education at the University of Florida School of Music. He also serves as chair of the faculty for the UF College of the Arts; convenor of the Assessment, Measurement, and Evaluation Special Interest Group for the International Society of Music Education; and chair of the International Symposia on Assessment in Music Education. He teaches undergraduate and graduate courses, including sections of the “Assessing Music Learning” course in the online Master of Music in Music Education (MMME) program. Before coming to UF, he taught high school choir and music theory.

For Dr. Haning, one of the most rewarding aspects of his role as an educator is helping students build new understandings and ideas. “It’s amazing to see how learning at one level can provide a foundation for learning at the next level,” he said.

In this Q&A, Dr. Haning answers some common questions about music learning assessment so that educators gain a better understanding of where to start and what techniques to consider.

Assessments are a crucial part of teaching. They help us guide our students’ progress and give us valuable data to inform our teaching.

I hope that we can move away from thinking of assessments as something that marks the end of learning and instead start thinking of them as something that moves learning along.

Done properly, assessments should be an iterative process, where we

1. Measure students’ understanding

2. Figure out where they need help

3. Give them that help

4. Measure them again

5. Celebrate how far they’ve come

It’s so important to have actual measurements and evaluations of individual students. For example, if all we do is listen to the choir during rehearsal, then we have little to go on in terms of planning our future teaching to help each student improve. But if we measure the knowledge and skills of individual students and determine that some are really struggling with solfege and others need help with their breath support, then we can target our lessons to make sure that all students are getting help in the areas that are most needed.

A note on the use of “assessment”: I’ve actually started to move towards the words “measurement” and “evaluation,” to try to be clearer about what we’re actually talking about — what we’re really trying to do when we assess students is measure their performance on a given task, and then evaluate that measurement, in order to determine what it means and the best way to move forward. Without the measurement, it’s hard to make an accurate evaluation — it’s important that we not leave out that step!

I’ll continue to use “assessment” for the purposes of our conversation here, but keep in mind that I’m always speaking with those two processes in mind.

The best place to start is with clear learning goals.

Assessments are about measuring a student’s ability to meet goals, and if you only have vague, group-based goals, such as “the band will play this piece successfully,” there’s not a lot to measure!

I always encourage teachers to take a good look at their learning goals before they start thinking about assessments. A well-written goal will almost assess itself.

Two questions to ask yourself are:

1. What do I actually need students to demonstrate they know or can do?

2. What are creative ways for students to show they have that particular knowledge or skill?

If, for example, my students need to show they understand the characteristics of the Baroque period, I could have them explore how to play a folk tune they already know in a Baroque style, or identify the Baroque piece in a set of three examples, or write a short piece of their own with Baroque characteristics.

Another place to start is with NAfME. Their Music Standards should be goals for all our classrooms. To go along with those standards, NAfME has developed a set of “Model Cornerstone Assessments” that individual teachers can adapt to meet their specific classroom needs.

Finally, if you’re still having trouble with assessment, consider taking classes, or seeking out professional development. You can often seek professional development at the district level; very few principals are likely to complain if you tell them you want to take a class that helps you assess better!

Or, you can look into academic classes like those in UF’s online Master of Music in Music Education program. There are also lots of great articles in professional journals, webinars, books, and other resources out there — the most important thing is that you’re actively working to build your knowledge.

It’s true that assessments take time. However, it’s a misconception that assessments must be overly long, complicated, or intense.

Anything that allows us to measure students’ ability can be an assessment, and in many cases a three-minute bellringer can be more effective than a 25-minute quiz.

Assessments are most effective when they are embedded in what you’re already doing. They can even make use of what would have been unused time.

Here are some ways I strategically use assessments:

These allow me to gauge the student’s understanding quickly, and it also allows me to keep them on task during the down time of a rehearsal. I’m capturing time where they would just be sitting and talking, or leveraging activities that I would have them do anyway, and I’m using that time to get assessment data.

Remember: we assess students to make sure they are learning and growing — if you don’t have time for that, what are you making time for?

One of our unique challenges as music educators is to take things that are inherently subjective and assign measurements (usually numbers) to them. Any tool that lets us create a measurement from something that is not obviously “measurable” is useful for music teachers.

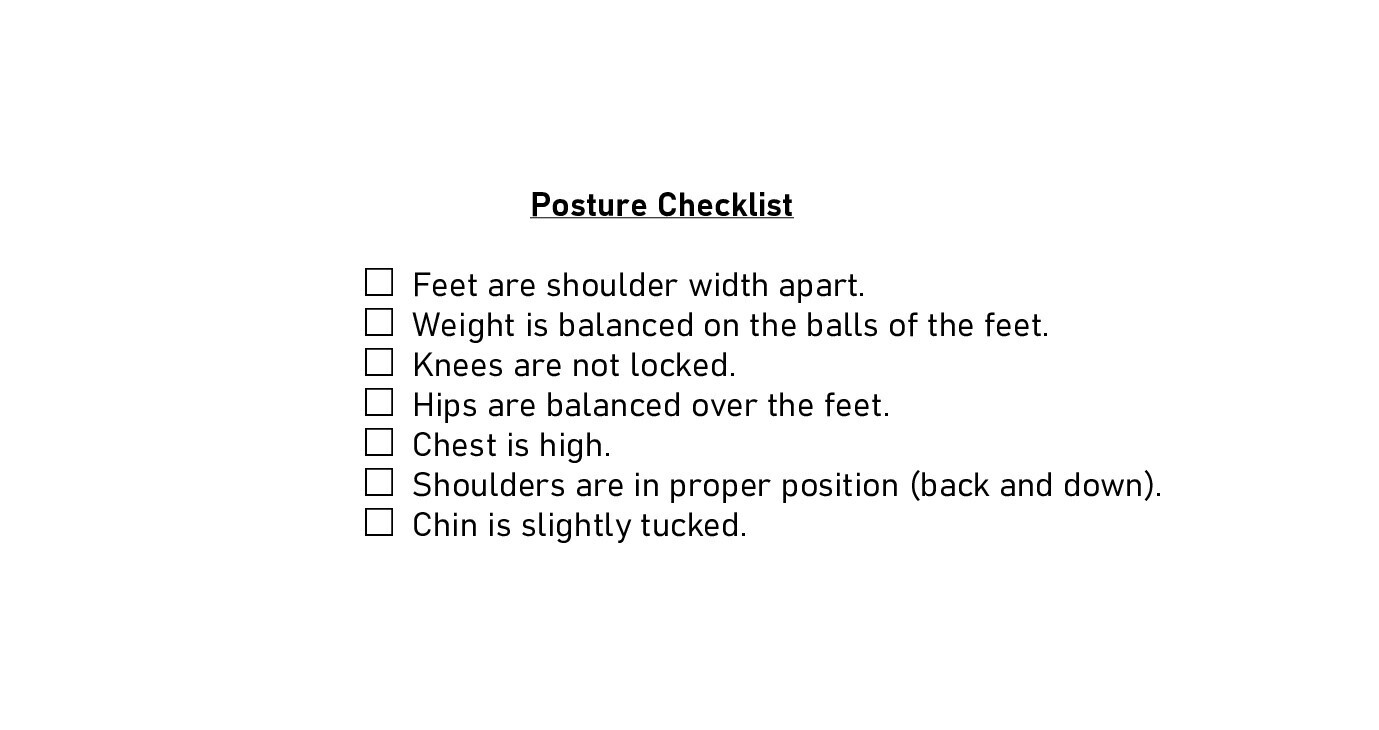

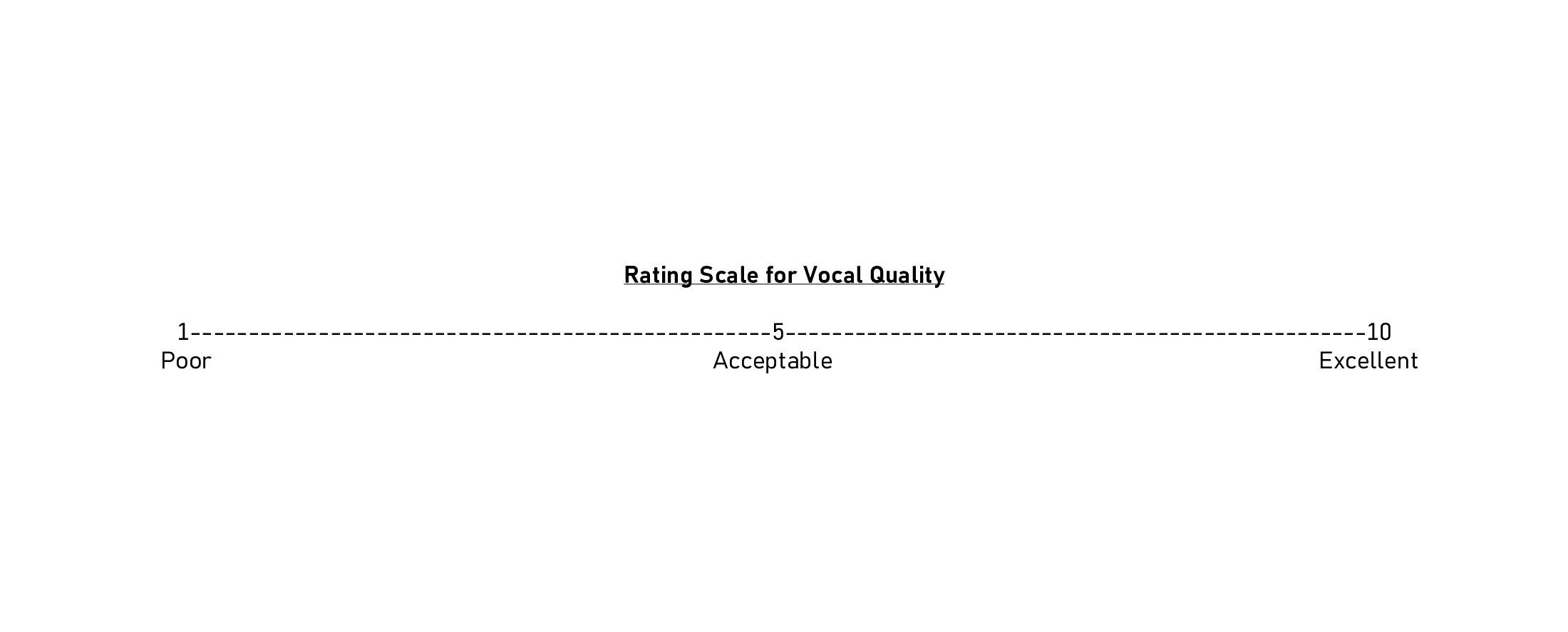

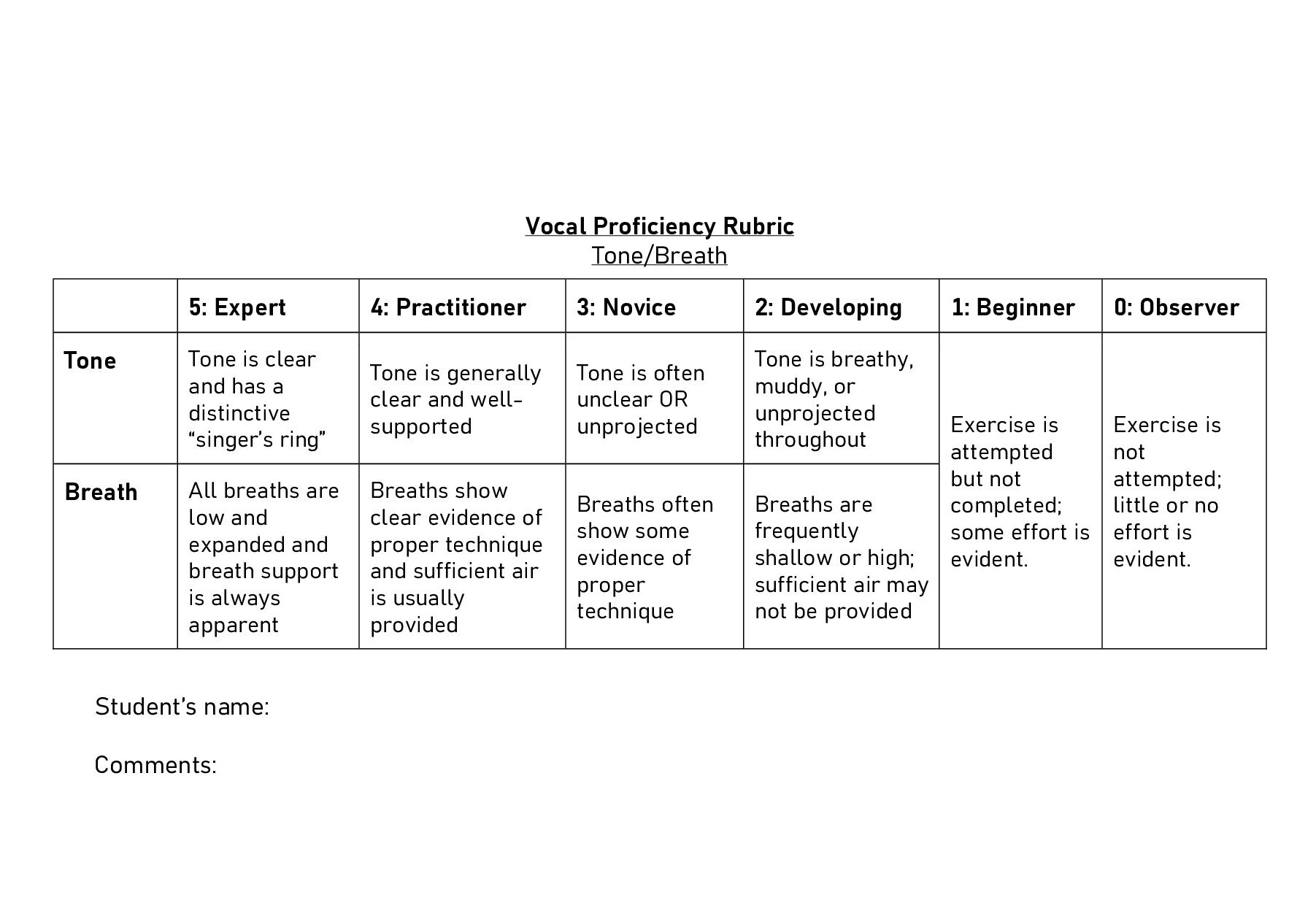

Some of the primary tools we use for this are checklists, rating scales, and rubrics. These are flexible, multi-situational tools that you can use to put a number on a moment.

A big advantage of rubrics is that they provide automatic suggestions for students on how to improve; students just have to look at the description for their score and for the next higher score to know what they should work on.

Keep in mind: one of the most challenging words you can add to a rubric is “and.” For example, if you write that students will score a 2 if they achieve “acceptable resonance and placement,” then what do you do if they have poor resonance but outstanding placement?

The clearer and more precise you can be, the quicker and less overwhelming your assessments will be.

You can see an example checklist, rating scale, and rubric below.

Checklist example

Rating scale example

Rubric example

All these tools can be used in a variety of different contexts. For example, you could use a checklist to make sure the student knows how to set up their instrument properly; use a rating scale for their overall performance on a piece; and use a rubric to dig into breath support, tone, quality, and expression.

A great tool for summative assessment is a digital/electronic portfolio. Portfolios allow us to provide evidence of student learning that goes beyond our own interpretation and gives us a chance to really show in a concrete way what students can do from the start of the year to the end of the year. Pair it with a rubric and you have a multimedia, multipurpose assessment.

No matter what tool you choose, make sure that your measurement instrument is as efficient and as clear as possible.

I’ve heard teachers say they refuse to assess their students because if they did, the students would become discouraged and quit music. If that’s true, then you’re doing assessment wrong!

Assessment should be a way that students see how far they’ve come and where they need to do to continue to improve. Done right, assessments do the opposite of discourage — they can motivate. Students understand they can reach another level and have a clear path to get there. They have motivation to grow as a musician and a creative person.

When we assess frequently and make it a normal part of the learning process, students come to take it for granted and see it as a valuable tool for continued improvement. It’s when we make assessments something that happens infrequently, under high stakes, and with no connection to our normal teaching, that it becomes something that students are afraid of.

Plus, by measuring a student’s progress and showing them a path to growth, we are telling them that music is a subject worth learning and worth improving in, just like math, or writing, or any other subject in school.

Ultimately, the teacher sets the attitude for the students. If you celebrate students’ progress and encourage them to keep moving forward, students will be happier about the assessment process.

Assessment isn’t talked about a lot in many music education programs. At UF, we want to be sure our master’s students get a thorough grounding in ideas and strategies related to assessment because it’s a crucial part of teaching. That’s why we’ve included an entire course on assessment as a part of the Masters in Music Education program, and it’s why we embed assessment throughout the program in all of our courses.

Embedding key concepts is part of a larger goal: while certain topics are foregrounded in certain courses, they’re also reinforced throughout your entire coursework.

We try hard to model effective assessments all the way through our program. Most of our assignments and all our courses have clear rubrics. Students can see what they’re going to be assessed on and the rubrics reflect what we feel is most important about the assignments.

So, not only are we expecting MMME students to apply these ideas all the way through the program, we as faculty are also trying to demonstrate the use of those items all the way through the program.

The University of Florida’s online Master of Music in Music Education program is designed to help music educators enhance their abilities as musicians, teachers, and passionate students of one of humanity’s most dynamic modes of creative expression. Exploring both practical and theoretical perspectives, the program, designed and taught by experts in the field, is perfect for current music educators looking to enhance their ability to encourage student engagement with music.

To learn more about the University of Florida’s online Master of Music in Music Education and download a free brochure, fill out the fields below. You can also call (352) 662-3395 to speak to an enrollment specialist.